Chau Hen’s Story: “I was a Farmer simply fighting for my land"

by SARA COLM

|

"They violate the rights of the ethnic minorities. We have no right to protest about the confiscation of our land. If I demand my land back, they say I want to overthrow the government, start a political movement.”

- Chau Hen, after fleeing Vietnam in 2008 |

|

Background

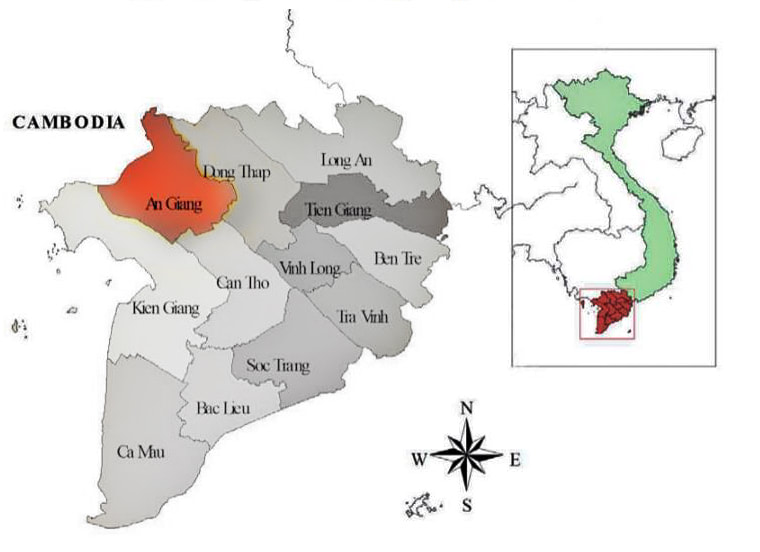

Chau Hen, 64, a member of the Khmer Krom ethnic minority group, was detained and severely tortured by police in 2010 after he returned to Vietnam from Thailand, where UNHCR had rejected his claim for refugee protection. A farmer and land rights activist in the Mekong Delta province of An Giang, Chau Hen organized peaceful protests against land confiscation in his village. He also led contingents from his village to participate in larger land rights protests in Saigon, together with farmers from more than half a dozen provinces. On April 7, 2008 Chau Hen and hundreds of other farmers from his village protested the destruction of a bridge leading to their rice fields by local authorities. That night at 2 am, ten truckloads of riot police, as well as some soldiers, surrounded the village. Firing shots into the air and using tear gas, they broke into the home of Chau Hen and another villager suspected of being ringleaders. Finding that the two men had fled already, police ransacked their homes and severely beat their family members with wooden and electric batons. Chau Hen and his wife fled to Cambodia and then Thailand to seek political asylum. In 2009 UNHCR rejected their asylum request, stating that at most Chau Hen might face “heavy monitoring” and even “some level of detention” if he returned to Vietnam, but nothing that would “rise to the level of persecution.” On December 17, 2010, Chau Hen and his wife returned to Vietnam, where he was arrested within half an hour of arriving back at his village. (Read more.) |

An Interview with Chau Hen, December 2015Arrest and Detention

After UNHCR rejected my request for refugee status, I left Bangkok and returned to Vietnam on December 17, 2010. Less than 30 minutes after arriving back in my village, police on more than ten Honda motorcycles arrived and arrested me. The police did not show any arrest warrant. I was already a wanted person, from before [leaving Vietnam]. I showed my UNHCR documents to them and told them I was not involved in any political activity in Cambodia. The reason I’d left Vietnam was because they’d mistreated me and taken my land. They took me to the commune police station for about 15 minutes, and then to the district detention center. I was held for almost four months in a dark cell with no windows, enclosed behind two levels of steel doors. During this time I had no contact with my family, no legal representation. I never left the cell other than for interrogation. When they took me out for interrogation first they handcuffed me through the metal slot in the door, and four police escorted me to interrogation. They were afraid I’d attack them. Interrogation and Torture Throughout my detention, they called me for interrogation every three or four days. In the interrogation room there were all sorts of torture instruments laid out on the table, including an electric shock device, a battery, and a large truncheon. The interrogation was usually conducted by district officials, with provincial officials participating at times. Even though I spoke some Vietnamese, I did not know the legal or political terms. Every interrogation I demanded a translator and they provided one. There were different translators. One of the translators was not very competent. He was very young and inexperienced and hadn’t gone to school beyond grade 12; his translation was unclear. Another was a Khmer from my district who was a three star provincial police officer who joined the district investigation. He spoke very harshly to me during interrogation, and threatened me. The first level of interrogation was by a provincial judicial police officer. He was the main interrogator. He would threaten me, then leave the room while others came in and beat me. He said he would help me — his purpose was to help me by collecting the truth. “If you don’t answer, you’ll be beaten,” he told me. He would show the torture devices to me, and ask which one I wanted to have. I said, if you don’t trust me, if you don’t believe I’m a farmer simply fighting for my land, just shoot me. If you think I oppose the government, don’t take your time to torture me, just finish me off with a bullet. I wasn’t a political dissident, my problem was a land problem. This had been my land since my ancestors’ time — thousands of years. We were struggling for our land. When I said this, the two-star interrogator grabbed me by the throat and slammed me against the wall. During interrogation they often beat me unconscious – they would hit me with their hands, slap me on my face, grab me by the neck and choke me, and pick me up and smash me against the wall. One time they punched me in the center of my chest. I lost consciousness and there was blood all over my body. The interrogators would ask me which groups or parties I served in Cambodia, what contact I had with overseas groups such as Khmer Krom Federation (KKF). I said that I wasn’t involved with any political groups but only demanded our land and the right to our culture, education, etc. They had Vietnamese language documents and photos sent from Phnom Penh pertaining to the KKF, with information about specific KKF leaders that they read to me. They asked if I knew these KKF members. I said I didn’t know them, I only knew Venerable Tim Sakhorn, who only carried out humanitarian work—human rights, land issues, helping intervene for Khmer Krom. There were more than 40 pages of notes summarizing my interrogation sessions. The final indictment was more than 30 pages. Everything was in Vietnamese. What I learned was that the more you answered, the more you talked, the more beatings you got. If you are ignorant you might talk too much and have to endure more beatings. It’s better if you talk less. Many prisoners die during torture by the police. Other prisoners told me to endure the beatings. “Don’t talk back or they will kill you,” they told me. Beatings, Torture, Injections

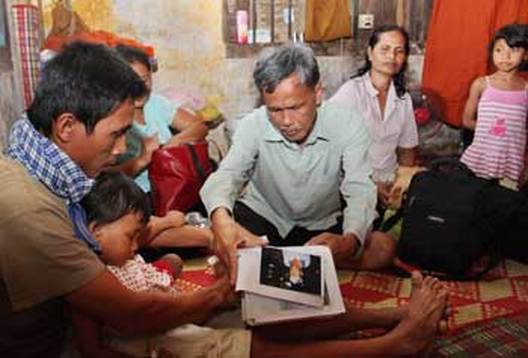

I came close to death twice during my time in prison. The first time was around April 2011, when I was at the district detention center. Police beat me unconscious during interrogation and I lost a lot of blood. They thought I was going to die and took me to a room within the prison complex – it was like a morgue. The room was completely empty, and seemed like a place to lay out dead bodies. There were no people there -- no staff, no patients. They offered no medical treatment other than hooking me up to an IV, then locked me in the room and left me completely alone to die. No staff came to check on me, nor did they give me any food. I think they didn’t want me to die in my cell, so they moved me to that room, just for appearances. I was there for one day. When they saw me come to and open my eyes, they seemed surprised. They sent me back to my cell. I don’t know what they injected me with, but it left me unable to speak or think clearly. It was if I had lost my soul and didn’t know myself. The second time I came very close to death was in June 2011, when I was at An Giang provincial prison. There is a photograph showing me shackled to the hospital bed at the provincial hospital from that time. I had become very sick from a high fever, and had gone for 20 days unable to eat. My weight had dropped from 65 to 40 kilos (143 to 88 pounds) and I was too weak to walk. They decided to send me to the prison clinic. Four prisoners had to carry me to the clinic on a stretcher – the same stretcher they used for dead bodies -- as the police stood guard and looked on. I was at the prison clinic for about two days. The prison doctor was a police officer with the rank of two stars. I was unconscious. When I came to, he asked me what was the matter with me. I opened my mouth to respond, but was unable to speak. When I couldn’t answer, the doctor hit me in the mouth with a round piece of hard rubber. He knocked my teeth out, including a wisdom tooth. I lost so much blood I passed out. Because they thought I was about to die, they decided to send me to a private hospital outside the prison. They changed me from the prison uniform to regular clothes. At the private hospital, even though I was barely conscious, police guarded me and they shackled my ankles to the bed with metal cuffs. While I was unconscious at the private hospital, they hooked me up to an IV and injected me with unknown drugs because I was unable to take pills. My wife, who was allowed to visit me there, told me about this later. I spent about four days at the private hospital. After my wife was able to get me to eat some rice porridge, I regained a bit of strength so they sent me back to prison. The prison authorities don’t want people to die in the cell, so they send them to the prison clinic, or to the private hospital, to make it look like you are getting treatment. Even if you die on the way to the clinic, it looks better than dying in prison. Trial

On March 31, 2011, I was tried and sentenced at the provincial court in An Giang. On the day of my trial, they had to carry me in a stretcher to the vehicle that took me to the court, where four police officers carried me inside. I couldn’t stand on my own, I was too weak and thin. For most of the trial I wasn’t conscious, I kept falling asleep. I was physically unable to speak at that time. When I opened my eyes I could see my wife, but I could not speak. My hands were in handcuffs and my feet were shackled. The police had to hold me up when I was ordered to stand to listen to the judgement. It was like I was dead already. I didn’t know myself. They brought in many Khmer witnesses to say that I was the ringleader, protest leader, part of a political movement against the state. I did not have a lawyer. In fact, I was not fighting for any political agenda. I was just fighting for our right to the land, and to our culture. An Giang Provincial Prison After the trial police came to my cell and asked if I wanted to appeal my conviction. They told me if I appealed, I could hire a lawyer for 20 million dong (about US$1,000), which was impossible for me. At the time I was still very incapacitated, and physically unable to speak as a result of being beaten by police during interrogation and also because I had been injected with unknown drugs. They took my inability to speak as rejecting my right to appeal. I lost all my rights at that time because I couldn’t speak. There was no way I could represent myself. Finding the money to hire a lawyer was also impossible. With no appeal, they left my sentence at two years. At the provincial prison I was first placed in a cell with many people together – between 10 and 20 inmates. There was a little more room than the solitary confinement cell at the district jail, but it was still very crowded. After four months, when the period for any possible appeal was over, I was transferred to a larger group cell, which had 87 people, on two levels. There was a TV and fan. It was very crowded – sometimes fights would break out over space. We had to be careful when we moved our bodies – other prisoners would beat us, kick us. My family had to buy a mat for me, mosquito net also. There was not enough space for a regular size mat – I had to cut it so that it was only half a meter wide and 2 meters long. There were five toilets for 80 people, and one water tank with filthy water. We lived like animals. It was very, very difficult. For food, it was rice and vegetables. They provided no salt, no fish sauce. On the rare occasions that they gave us meat, it was a thin, papery slice of pork fat . Some air came into the cell from windows, which also let in the rain when it rained, making it difficult to sleep. They only let us out of the cell to work. We worked every day except Sunday, when we could rest. On Sundays they had us exercise for one hour outside in the courtyard to keep us moving and prevent us from having any health issues, such as our legs becoming numb. I was held together with really violent criminals -- murderers, drug addicts, robbers, arms traffickers. I was the only one with a good background – there were no other activists like me. Forced Labor The first several months at An Giang Prison I was too weak to work. When I had recovered my strength a bit, in July 2011 they sent me for a medical check-up and determined I was able to work. For me, this meant that after eight months confined in dark cells [at the detention center and then at An Giang Prison], finally I could leave the cell and see the sky and sunlight I understood I might get a three-month reduction in sentence if I went to work, was a good worker, and didn’t take drugs or fight with other prisoners. First I worked in the prison rice fields, carrying rice bags. The prison rice fields were huge. There were thousands, maybe tens of thousands of prisoners working there. We worked 9.5 to 10 hours a day. The bags weighed 65-70 kilos (143-154 pounds) and we had to carry them through the muddy paddies, with water up to our knees. It was difficult walking through mud and water – I fell down often. But I had to do it. While we worked, police completely surrounded the area, guarding us. |

"The first time I was allowed to visit him, he could not open his eyes to look at us, and it seemed he could not hear us or understand what we said to him. He was unable to speak or to answer us. His health condition made us think he was either injected with anesthetic, or was somehow traumatized -- he just sat there motionless, despite my many questions. At the trial, he could not move and did not recognize his wife and children. He fainted many times.”

- Chau Hen's wife, Neang Phon, describing his condition two days before his trial in 2011. “All I wanted was freedom for Khmer Krom, a resolution of our land problems, freedom of religion, the right to study our own language and follow our own cultural traditions, and the right to the same education as Vietnamese people.”

- Chau Hen in an interview in 2015, after resettling to the United States |