Voices: Survivors of Torture

|

Torture Survivor Stories: |

“Every time they would ask me a question about my husband and I said I didn’t know, they would shock me with the electric device. I do not remember exactly how many times I was shocked by this electric device, but it was many times.” —An ethnic minority woman from Lam Dong province who was tortured by police demanding information about her husband's political activities |

Torture Survivor Stories

|

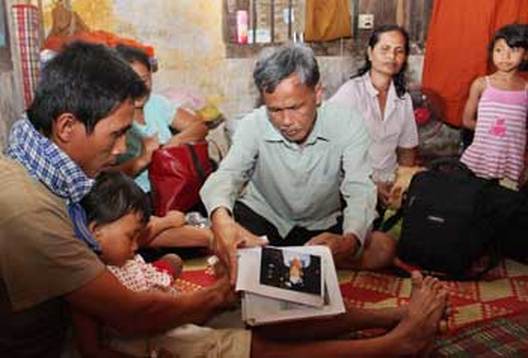

Khmer Krom Land Rights Activist Chau Hen

by SARA COLM Chau Hen, 64, a member of the Khmer Krom ethnic minority group, was imprisoned and severely tortured by police in 2010 after he returned to Vietnam from Thailand, where UNHCR had rejected his claim for refugee protection. A farmer and land rights activist in the Mekong Delta province of An Giang, Chau Hen organized peaceful protests against land confiscation in his village. He also led contingents from his village to participate in larger land rights protests in Saigon, together with farmers from more than half a dozen provinces. (Read more.) |

Catholic Parishioner Tran Thanh Tien: Protecting Sacred Space

by SARA COLM

Tran Thanh Tien was among 62 people in his village who were arrested and severely beaten by police in May 2010 for participating in a funeral procession and protest march to a cemetery located on disputed land in Da Nang.

Police shocked him with an electric baton and beat him in his chest and arm pits from 3 pm until 10 pm. When he passed out, they threw soapy water on him. They hit him on his back with hardened plastic kitchen stools. They hung him by his handcuffed wrist from the window ledge for an entire afternoon, beating him as he hung there. After his release, when he refused to report on other villagers, police beat him again.

“There were two men beating me, one on each side. They boxed both ears, one ear then the other. They hit me with their fists, and slapped me. They beat me so hard that the inside of my body still hurts today.”

“Before this happened to me, I never heard of any torture in police stations before this. Nobody dares to speak about it. I realized that people who are tortured by the police don’t dare speak about it.

“I never imagined I’d be beaten like that. This is our tradition in burying the dead, to send them to the last place. I never expected police to crack down on a funeral procession like that.

“The last words the police told me were, we know you are a farmer, you are a strong man. We guarantee that after you are released you will not be able to farm anymore.

“In fact, it’s true. Since I was released I don’t feel very well. I have chest pains, back pain, coughing, and blurred vision. My ears ring and I have hearing problems. I can’t carry heavy weights any more – the police pulled my muscle when they handcuffed my hand and hung me by my wrist from the window ledge, beating me on my knee joints and groin.

“Sometimes when I’m tired I have nightmares. The fear goes back to my mind. When I have that dream I can’t get up, I’m so weak with fear— it takes two or three hours to recover. After the nightmare it’s several hours before I can move or get up.”

UPDATE: In 2012 Tran Thanh Tien resettled as a refugee to the United States, where he testified before Congress in April 2013 about police torture and abuse of people from his village in Da Nang.

by SARA COLM

Tran Thanh Tien was among 62 people in his village who were arrested and severely beaten by police in May 2010 for participating in a funeral procession and protest march to a cemetery located on disputed land in Da Nang.

Police shocked him with an electric baton and beat him in his chest and arm pits from 3 pm until 10 pm. When he passed out, they threw soapy water on him. They hit him on his back with hardened plastic kitchen stools. They hung him by his handcuffed wrist from the window ledge for an entire afternoon, beating him as he hung there. After his release, when he refused to report on other villagers, police beat him again.

“There were two men beating me, one on each side. They boxed both ears, one ear then the other. They hit me with their fists, and slapped me. They beat me so hard that the inside of my body still hurts today.”

“Before this happened to me, I never heard of any torture in police stations before this. Nobody dares to speak about it. I realized that people who are tortured by the police don’t dare speak about it.

“I never imagined I’d be beaten like that. This is our tradition in burying the dead, to send them to the last place. I never expected police to crack down on a funeral procession like that.

“The last words the police told me were, we know you are a farmer, you are a strong man. We guarantee that after you are released you will not be able to farm anymore.

“In fact, it’s true. Since I was released I don’t feel very well. I have chest pains, back pain, coughing, and blurred vision. My ears ring and I have hearing problems. I can’t carry heavy weights any more – the police pulled my muscle when they handcuffed my hand and hung me by my wrist from the window ledge, beating me on my knee joints and groin.

“Sometimes when I’m tired I have nightmares. The fear goes back to my mind. When I have that dream I can’t get up, I’m so weak with fear— it takes two or three hours to recover. After the nightmare it’s several hours before I can move or get up.”

UPDATE: In 2012 Tran Thanh Tien resettled as a refugee to the United States, where he testified before Congress in April 2013 about police torture and abuse of people from his village in Da Nang.

Buddhist Monk Kim Muon: Religious Freedom Activist

by SARA COLM

Ven. Kim Muon, a Khmer Krom Buddhist monk, was forcibly defrocked, expelled from the monkhood, and imprisoned in Soc Trang province in 2007 after participating in a protest with 200 other monks calling for religious freedom.

“When you enter the interrogation room, you feel very afraid. There was a table and chair; windows but they did not open. There were two people in the room. The one who asked the questions was not the one who beat me. He would call the others in to beat me.

“Every time I was interrogated, they beat me. They used a water bottle to hit me under my arms, on both sides. I must raise my arms, or they would hit me in the face.

“They smashed my head against the wall. The wall had been specially made, with concrete lumps in it, for torture.

“During interrogation they would use different methods if I did not confess. Sometimes they put a rug on my head to smother me. They would make me eat dog meat, which as a monk I cannot eat. Or they would put underwear on my head. They insulted and cursed me, tried to make me mad. They said I’d become a monk in order to become involved in politics.

“Sometimes they took my head and pushed it into water until I was unconscious. Two people held my arms on each side and pushed my head down.

“Afterwards, we have to sign the confession that they wrote up themselves. My writing was not clear because I was in handcuffs. So they took my hand and forced me to sign.”

UPDATE: After his release from prison in 2009, Ven. Kim Muon fled Vietnam and was resettled as a refugee in the United States, where he continues to advocate for religious freedom and cultural rights for Khmer Krom people.

by SARA COLM

Ven. Kim Muon, a Khmer Krom Buddhist monk, was forcibly defrocked, expelled from the monkhood, and imprisoned in Soc Trang province in 2007 after participating in a protest with 200 other monks calling for religious freedom.

“When you enter the interrogation room, you feel very afraid. There was a table and chair; windows but they did not open. There were two people in the room. The one who asked the questions was not the one who beat me. He would call the others in to beat me.

“Every time I was interrogated, they beat me. They used a water bottle to hit me under my arms, on both sides. I must raise my arms, or they would hit me in the face.

“They smashed my head against the wall. The wall had been specially made, with concrete lumps in it, for torture.

“During interrogation they would use different methods if I did not confess. Sometimes they put a rug on my head to smother me. They would make me eat dog meat, which as a monk I cannot eat. Or they would put underwear on my head. They insulted and cursed me, tried to make me mad. They said I’d become a monk in order to become involved in politics.

“Sometimes they took my head and pushed it into water until I was unconscious. Two people held my arms on each side and pushed my head down.

“Afterwards, we have to sign the confession that they wrote up themselves. My writing was not clear because I was in handcuffs. So they took my hand and forced me to sign.”

UPDATE: After his release from prison in 2009, Ven. Kim Muon fled Vietnam and was resettled as a refugee in the United States, where he continues to advocate for religious freedom and cultural rights for Khmer Krom people.

Montagnard Christian Rmah Plun: Punished for Seeking Asylum

by SARA COLM

Rmah Plun, a Montagnard (Jarai) Christian from Gia Lai province, fled to Cambodia in 2004, where he was recognized as a refugee by UNHCR. In May 2005, though Plun was eligible for resettlement abroad, he decided to return to Vietnam because he missed his family.

After crossing the border to Vietnam, Vietnamese police processed him for two hours and then sent him and five other returnees directly to the provincial prison in Gia Lai, where they arrived around midnight. He was detained in a dark cell for three days, his hands tied even when he was given food. Police interrogated him every day about why he had left Vietnam, pressured him to renounce his religion, and beat and tortured him. During his first interrogation session the police asked him why he went to Cambodia. “I told them I fled because I was afraid the police would beat me,” he said. “As a response, they punched me in the face with their fists four times.”

During subsequent interrogation sessions Plun was beaten in the chest, back and groin; kicked in the shins with army boots; and slapped in the face. Police also inserted writing pens between his fingers and then tied his hands tightly with a rope, squeezing his fingers and causing excruciating pain.

"When I was finally allowed to return to my village and see my wife, she was shocked by how swollen and bruised my face was," Plun said. A month later, he was arrested again and tortured. He was detained for five nights in a dark cell and repeatedly pressured to renounce his religion and to provide names and locations of Montagnards in hiding.

During interrogation sessions, police forced him to lie down with his hands and feet raised in the air by ropes for three hours. If he dropped his hands or feet, he was beaten. He was also hung upside down by his feet for 30 minutes at a time. After five days he was released and placed under house arrest. Police were stationed outside his house every night, he could not leave even to work on his farm, and he was not allowed to gather with others for church.

UPDATE: In December 2005 Rmah Plun fled to Cambodia a second time. In September 2006 he died in the UNHCR refugee camp in Phnom Penh at the age of 31.

by SARA COLM

Rmah Plun, a Montagnard (Jarai) Christian from Gia Lai province, fled to Cambodia in 2004, where he was recognized as a refugee by UNHCR. In May 2005, though Plun was eligible for resettlement abroad, he decided to return to Vietnam because he missed his family.

After crossing the border to Vietnam, Vietnamese police processed him for two hours and then sent him and five other returnees directly to the provincial prison in Gia Lai, where they arrived around midnight. He was detained in a dark cell for three days, his hands tied even when he was given food. Police interrogated him every day about why he had left Vietnam, pressured him to renounce his religion, and beat and tortured him. During his first interrogation session the police asked him why he went to Cambodia. “I told them I fled because I was afraid the police would beat me,” he said. “As a response, they punched me in the face with their fists four times.”

During subsequent interrogation sessions Plun was beaten in the chest, back and groin; kicked in the shins with army boots; and slapped in the face. Police also inserted writing pens between his fingers and then tied his hands tightly with a rope, squeezing his fingers and causing excruciating pain.

"When I was finally allowed to return to my village and see my wife, she was shocked by how swollen and bruised my face was," Plun said. A month later, he was arrested again and tortured. He was detained for five nights in a dark cell and repeatedly pressured to renounce his religion and to provide names and locations of Montagnards in hiding.

During interrogation sessions, police forced him to lie down with his hands and feet raised in the air by ropes for three hours. If he dropped his hands or feet, he was beaten. He was also hung upside down by his feet for 30 minutes at a time. After five days he was released and placed under house arrest. Police were stationed outside his house every night, he could not leave even to work on his farm, and he was not allowed to gather with others for church.

UPDATE: In December 2005 Rmah Plun fled to Cambodia a second time. In September 2006 he died in the UNHCR refugee camp in Phnom Penh at the age of 31.

Writer Tran Khai Thanh Thuy: Denial of Lifesaving Medication

by SARA COLM

At Detention Center No. 1 (Hoa Lo) in Hanoi, dissident writer Tran Khai Thanh Thuy came close to death when she was deprived of medication she must take every day for diabetes and tuberculosis.

“In Hoa Lo, they took my medicine away. I was without my medicine for diabetes and TB for one month and four days, from October 8 until December 2009. They were fully aware of the consequences. For my diabetes I must take two pills in the morning and two in the evening. If no medicine, it can kill you. Without my medicine, I was totally exhausted. They came to my cell eight times to provide ‘ER’[critical care]—that means they gave me two paracetamol.

“It was very dangerous. I was sweating profusely, my lips turned black, my arms and legs were very heavy. I felt I could die at any time. My blood pressure jumped up, and it was impossible to control my bladder. Without my medicine I had no control over urination. I had to go to the toilet dozens of times a day; sometimes I was going constantly. At times I had to pee into my rice bowl.

“The diabetes affects my nerves. I had strong headaches and it was impossible to sleep. My only resort was to yell throughout the night.”

UPDATE: In June 2011, Tran Khai Thanh Thuy resettled as a refugee to the United States, where she continues to write.

by SARA COLM

At Detention Center No. 1 (Hoa Lo) in Hanoi, dissident writer Tran Khai Thanh Thuy came close to death when she was deprived of medication she must take every day for diabetes and tuberculosis.

“In Hoa Lo, they took my medicine away. I was without my medicine for diabetes and TB for one month and four days, from October 8 until December 2009. They were fully aware of the consequences. For my diabetes I must take two pills in the morning and two in the evening. If no medicine, it can kill you. Without my medicine, I was totally exhausted. They came to my cell eight times to provide ‘ER’[critical care]—that means they gave me two paracetamol.

“It was very dangerous. I was sweating profusely, my lips turned black, my arms and legs were very heavy. I felt I could die at any time. My blood pressure jumped up, and it was impossible to control my bladder. Without my medicine I had no control over urination. I had to go to the toilet dozens of times a day; sometimes I was going constantly. At times I had to pee into my rice bowl.

“The diabetes affects my nerves. I had strong headaches and it was impossible to sleep. My only resort was to yell throughout the night.”

UPDATE: In June 2011, Tran Khai Thanh Thuy resettled as a refugee to the United States, where she continues to write.

Democracy Activist Bui Kim Thanh: Defending Victims of Injustice

by SARA COLM

Bui Kim Thanh was a lawyer and member of the banned Democratic Party of Vietnam who defended victims of land confiscation. She was arrested by police and involuntarily committed to mental hospitals three times, in 1995, 2006, and 2008.

Her arrest and involuntary psychiatric detention in November 2006 was part of a broader government crackdown on activists prior to the visit to Vietnam of U.S. President George Bush. "They were worried I might incite or encourage the victims of land conflicts to protest when Bush came,” she said. During eight months’ stay at Central Psychiatric Hospital No. 2 in Bien Hoa, she received no therapy or counseling, but was forced to take injections three times a day.

“I tried to ask what the injection was, but they would not tell me. The effect of the injection was either I immediately passed out unconscious, or I felt as if paralyzed. Afterwards, there were more reactions: drooling, stiff neck, my whole body was paralyzed, sometimes I passed out….Whenever I objected to the injection, they tied me to my bed with cords for a few hours.”

Her detention at Bien Hoa was primarily punitive in nature, she said, with virtually no therapeutic value.

“During my time at Bien Hoa, I received no counseling whatsoever. They never told me anything about the legal basis for my detention there. They themselves knew there was nothing wrong with me.”

The only time she saw a doctor was the morning after she was admitted, for a session that lasted less than ten minutes.

“His first—and only—question was, ‘Why are you inciting the victims of land injustice to have demonstrations?’ I answered, ‘Why do you not ask me how I feel? After the medication and treatment yesterday, why do you think I can incite anyone? Do you ask this because the police prompt you to do so?’

“He was very unhappy with my response and said, ‘In that case, go back to your room.’”

She was put into an isolation cell where staff could observe her from outside. A sign on the door read: “No one allowed to contact [this patient] without written authorization of the People’s Procuracy of Ho Chi Minh City, the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Committee, and the Ho Chi Minh City police.”

Later they moved her to another room, where she stayed the rest of the time.“The room was five feet by six feet—enough room for a regular iron bed, a small space to stand, and a toilet. There was no mattress or mosquito net. My family brought me a straw mat and later they were allowed to bring a mosquito net and a blanket.

“There was no window in the room, only an opening with bars on the door—some air came in that way. A small light was turned on when darkness fell but it was not reliable because of power outages. The toilet was very dirty—there were rats, maggots.”

She was not allowed to have newspapers, books, or even paper. Her pen was confiscated at the order of the doctor. She was allowed visitors once a week, though they needed permission from police to visit and were accompanied by police the whole time. Her husband came under pressure from authorities to convince her to pledge not to continue her social activism.

“They used my husband to pressure me to sign a paper agreeing not to speak out for victims of land injustice. ‘If I’m supposed to be crazy, why would I sign?’ I said. ‘I’m supposed to be mentally incompetent.’ I refused to sign.”

After four months confined to her room, her family submitted a petition requesting that she be allowed out of the room. The authorities then let her leave her room, but only at night.

“At first they didn’t want to let me out of the room at all, but my husband and kids wrote a petition. After four months there, I had lost 17 kilos and was so weak that my family insisted, submitted a petition. Then they only let me out at night, not during day time—this was after four months in the room.”

After her release from Bien Hoa in July 2007, Bui Kim Thanh continued her advocacy on behalf of petitioners despite being monitored and harassed by police. In August 2007 she was detained by police, who had a psychiatrist present during her interrogation. In February 2008, she was briefly detained again after she joined many other dissidents at the funeral of veteran dissident Hoang Minh Chinh.

Less than two weeks later, on March 6, 2008, police arrested her, forced her into a police car, and involuntarily committed her to Bien Hoa again. Diplomatic pressure led to her release four months later.

UPDATE: On July 21, 2008, Bui Kim Thanh left Vietnam and resettled in the United States.

by SARA COLM

Bui Kim Thanh was a lawyer and member of the banned Democratic Party of Vietnam who defended victims of land confiscation. She was arrested by police and involuntarily committed to mental hospitals three times, in 1995, 2006, and 2008.

Her arrest and involuntary psychiatric detention in November 2006 was part of a broader government crackdown on activists prior to the visit to Vietnam of U.S. President George Bush. "They were worried I might incite or encourage the victims of land conflicts to protest when Bush came,” she said. During eight months’ stay at Central Psychiatric Hospital No. 2 in Bien Hoa, she received no therapy or counseling, but was forced to take injections three times a day.

“I tried to ask what the injection was, but they would not tell me. The effect of the injection was either I immediately passed out unconscious, or I felt as if paralyzed. Afterwards, there were more reactions: drooling, stiff neck, my whole body was paralyzed, sometimes I passed out….Whenever I objected to the injection, they tied me to my bed with cords for a few hours.”

Her detention at Bien Hoa was primarily punitive in nature, she said, with virtually no therapeutic value.

“During my time at Bien Hoa, I received no counseling whatsoever. They never told me anything about the legal basis for my detention there. They themselves knew there was nothing wrong with me.”

The only time she saw a doctor was the morning after she was admitted, for a session that lasted less than ten minutes.

“His first—and only—question was, ‘Why are you inciting the victims of land injustice to have demonstrations?’ I answered, ‘Why do you not ask me how I feel? After the medication and treatment yesterday, why do you think I can incite anyone? Do you ask this because the police prompt you to do so?’

“He was very unhappy with my response and said, ‘In that case, go back to your room.’”

She was put into an isolation cell where staff could observe her from outside. A sign on the door read: “No one allowed to contact [this patient] without written authorization of the People’s Procuracy of Ho Chi Minh City, the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Committee, and the Ho Chi Minh City police.”

Later they moved her to another room, where she stayed the rest of the time.“The room was five feet by six feet—enough room for a regular iron bed, a small space to stand, and a toilet. There was no mattress or mosquito net. My family brought me a straw mat and later they were allowed to bring a mosquito net and a blanket.

“There was no window in the room, only an opening with bars on the door—some air came in that way. A small light was turned on when darkness fell but it was not reliable because of power outages. The toilet was very dirty—there were rats, maggots.”

She was not allowed to have newspapers, books, or even paper. Her pen was confiscated at the order of the doctor. She was allowed visitors once a week, though they needed permission from police to visit and were accompanied by police the whole time. Her husband came under pressure from authorities to convince her to pledge not to continue her social activism.

“They used my husband to pressure me to sign a paper agreeing not to speak out for victims of land injustice. ‘If I’m supposed to be crazy, why would I sign?’ I said. ‘I’m supposed to be mentally incompetent.’ I refused to sign.”

After four months confined to her room, her family submitted a petition requesting that she be allowed out of the room. The authorities then let her leave her room, but only at night.

“At first they didn’t want to let me out of the room at all, but my husband and kids wrote a petition. After four months there, I had lost 17 kilos and was so weak that my family insisted, submitted a petition. Then they only let me out at night, not during day time—this was after four months in the room.”

After her release from Bien Hoa in July 2007, Bui Kim Thanh continued her advocacy on behalf of petitioners despite being monitored and harassed by police. In August 2007 she was detained by police, who had a psychiatrist present during her interrogation. In February 2008, she was briefly detained again after she joined many other dissidents at the funeral of veteran dissident Hoang Minh Chinh.

Less than two weeks later, on March 6, 2008, police arrested her, forced her into a police car, and involuntarily committed her to Bien Hoa again. Diplomatic pressure led to her release four months later.

UPDATE: On July 21, 2008, Bui Kim Thanh left Vietnam and resettled in the United States.

The survivor accounts above are based on interviews conducted by Sara Colm for Human Rights Watch, the Campaign to Abolish Torture in Vietnam, Boat People SOS, and Amnesty International.